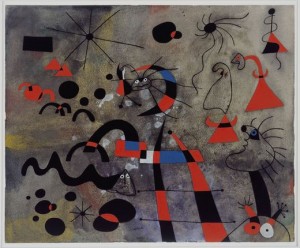

There’s a big Miró retrospective on at the Tate at the moment. It’s a fun exhibition, and clearly popular with kids. The paintings are arranged chronologically. The first room and a half works through the typical progression of a young artist trying on a series of different painting hats (“should I be a cubist, or what about a post-impressionist landscape, or if I …”), before he figures out the essentials of what a “Miró” is somewhere in his thirties. Miró then gets going painting Mirós, which he does very effectively for the rest of his life. Passing through the show you find the same core vocabulary of shapes — thorn-like triangles, slits with tendrils, a particular kind of squiggle, blobs and ladders running upwards — being continuously moved around on shifting backgrounds of colour. Sometimes they’re used in a doodley figurative way (the shapes have figurative roots in teeth, penises, vaginas, eyes etc.), and sometimes Miró just cuts them loose to float around by themselves. Generally he’s enjoying himself, which is nice to see.

Alongside this, the curator as you go from room to room is working like a demented ant to explain how, decade by decade, the paintings are a profound expression of each of the major events of the twentieth century. And so Miró’s shape-configurations variously speak movingly of the Spanish Civil War, the rise of fascism, the Second World War, the greater (American) freedoms of the fifties, the revolutionary spirit of ’68, and so on. The fact that you could very easily swap the paintings in say, room 9 with room 5, and have these sets of blobs be about New York, and those sets of blobs be about Franco, doesn’t seem to be acknowledged. On the contrary — the more abstract the work, the tighter the connections made with history, until in an apogee of preposterousness the curator suggests a birdish blob beneath a squiggle painted in 1939 actually prefigures the horror of the aerial bombardment of Europe (Miró’s interest in aviation is induced via a newspaper clipping found among his papers at the time). Were such a thing as a 2011 Miró to exist, it would no doubt immediately be welcomed as a stirring response to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Arab Spring …

The human capacity to make meaning given a set of loose shapes is endless and wonderful. I remember an incredible afternoon I spent lying on my back in Mexico watching cloud formations pass above me, and following an intense narrative of dinosaurs morphing into craggy bearded men, who in turn gave way to a field of skeletons riding horses, then replaced by a gigantic baby eating an entire train full of passengers reading newspapers in trilby hats …. We make meaning when we look at clouds, and in much the same way, we make meaning when we look at abstract or semi-abstract art. Only we think about the two very differently. It’s an example of “domain-dependent thinking” — or rather, it’s domain-dependent thinking about thinking, or domain-dependent philosophy. The core thought processes going on when lying on our backs beneath the sky and when visiting art galleries are themselves fairly similar, but the interpretation varies according to the domain. With the clouds we know it’s us who’s doing it — who’s making the meaning — but with art we always want to believe it’s the artist.

This causes a number of problems. Firstly it means we monumentalise certain artists for all sorts of things they haven’t really done per se — attributing to them greatness, extraordinary insight, fabulous evocative power etc., and generally using them to satisfy our desire to fawn. This is confusing and creates a lot of spurious markets and academic criticism. At the same time it leaves great droves of other artists — who quite legitimately point out their squiggles and blobs work equally well at suggesting meanings to viewers, especially if associated with a stirring date like 1939 — rather frustrated. And then quite how you sort one kind of artist from the other, the monumentalised from the repudiated, especially when the effects of their art aren’t technically in their own hands, is really very chancy. From the artist’s perspective it’s all a little disempowering and unpredictable.

One artist who remains blissfully free in spite of all this however is Aelita Andre. Andre, whose work is exhibited internationally and sells for tens of thousands of dollars, remains impervious to the traditional anxieties of the artist through virtue of being an infant. At three, her paintings at times hint tantalisingly toward figurative interpretations (kangaroos, eagles etc.), while at others they remain exuberantly free, guided as she is in her choices by simple things like: “squeezing tubes is fun”, “smooshing paint feels nice”, “I’m hungry now, let’s stop”.

And so she stops, and waddles into the next room, and is gathered up by her father for a bath. We linger to consider her paintings. Some of them are deeply evocative. They speak movingly of the current financial crisis, the onset of which coincides so compellingly with Andre’s birth. An eagle, the symbol of American economic imperialism, is seemingly shot in the eye by the sun, while a manichean chaos of black and white consumes its body …