Speech delivered at the House of Lords, London, 16 October 2012, for Vision

The trouble is, cities don’t whisper to each other about liking each other’s moves. Quite the opposite — they complain incessantly about congestion. They complain about how blocked up they are, how they need to cut traffic, how difficult transport is to manage, how expensive transport infrastructure is to build, how expensive it is to maintain, how it’s crumbling everywhere …. Once on a roll, they berate themselves further for being massively expensive on all fronts really, as well as being shot through with poverty, riddled with crime, racked by sickness, socially isolating and alienating, and often dirty to boot. The apparently endemic nature of all of these problems inevitably drags on the question, ‘Why build cities at all?’ Certainly governments for the most part have neither liked nor wanted them, and historically have tended to push for the development of towns and smaller cities over larger urban agglomerations. Yet in spite this, and all the costs and problems, big cities continue to mushroom. Why?

Alain Bertaud gives this explanation:

“large labour markets are the only raison d’être of large cities”

By this, the purpose of drawing together so many people in one place is to gain the competitive advantages of a large labour market, which, if well-managed, outweighs the costs of building the city. For the large market to work however, it needs to be unified (efficiency gains are lost as soon as the market starts to fragment — i.e. it starts to operate as multiple smaller markets, which together present the form and costs of a city, but without the benefits). The concept of labour market unity — and thereby the concept of the city — rests upon the assumption that any worker in the city is able to access any potential job, and reciprocally, any employer in the city is able to draw indiscriminately from across the pool of urban workers. After all, why have the workers on one side of the city in the same city as workers on the other side if they can’t both access the same labour opportunities? They might as well be in two separate smaller cities, which would be cheaper and easier to run.

This need for access lays out a very clear principle: the key for cities is mobility. Mobility is what allows large cities to do what they exist to do.

This theory is however incomplete, as cities are as much about consumption as they are about production. If we strike the word “only” from the above Bertaud quote, we can add the following condition:

large consumer markets are the corollary raison d’être of large cities

And again, the need for unity, and therefore mobility, is paramount. For businesses setting up in a large city, the reason to pay the higher rents involved (generated by the high costs city-building and city-upkeep), is to be able to access a large market of potential customers. And equally for customers, what the city offers is the advantage of a large number of providers of products and services all competing with each other. For the competition to work, the businesses must be on a level, such that any consumer from any part of the city is able to access any business in any other part of the city, or vice versa.

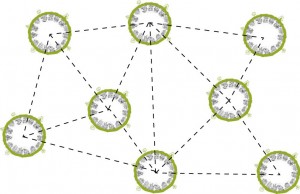

Curiously however, this fundamental need for all parts of the city to support mutual flows of movement is missed completely by the favourite urban form of urban planners, viz., the “village-within-a-city”, or “mixed-use self-sufficient development”. Repeatedly planning officials demand, and architects supply, developments within cities that balance the number of jobs with the number of residents with the number of shops — all in the hope that somehow people will work and live within the bounds of a little urban-village. When thought about however, this is a remarkably peculiar idea. The essential question, if you’re in a village-within-a-city, is why pay the extra rent of being in the city when you could be in a village well outside of the city? If all you’re doing is staying in the village, then why not be in a village in Shropshire? What possible advantage can there be to being huddled up next to all the other villages-within-the-city? Why bunch the villages at all? The only answer can be: so that you can get easily from one village to the next. I.e. the villages give ready access to each other, and support mutual flows (and thereby mutual competition and choice). And in that case, if the villages are all contiguous and free-flowing, how are they presenting anything other than a unified city? The concept of multiple villages just melts away.

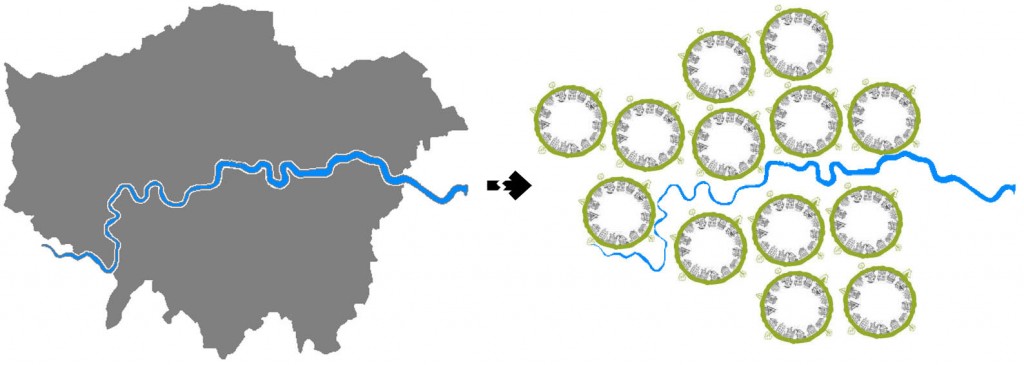

London as a unified large urban labour and consumer market is replaced by a cluster of “villages-within-the-city”. While the idea is a planners’ darling, there is no logical grounds for it, nor a credible example of it working.

Sure enough, this is what repeatedly happens when villages-within-cities are built. The “village” development itself may present carefully balanced mixed-use real-estate, but for the most part, those living within the “village” travel elsewhere in the city to work, while those working in the “village” travel in from other parts of the city where they live. This happens even in the extreme circumstances of satellite towns, where in a failed effort to cordon the new development off from the city, it is thrown geographically outside of it. Shanghai provides a perfect example: over the last decade, large-scale top-down government planning created a string of satellite towns outside the city proper, in the belief that this would ease congestive pressures. However far from staying put, the satellite residents commuted into Shanghai, the satellite workers commuted out from Shanghai, consumers went in both directions, and the satellites operated effectively as unified parts of the city — only at the far end of a set of artificially created congestion corridors.

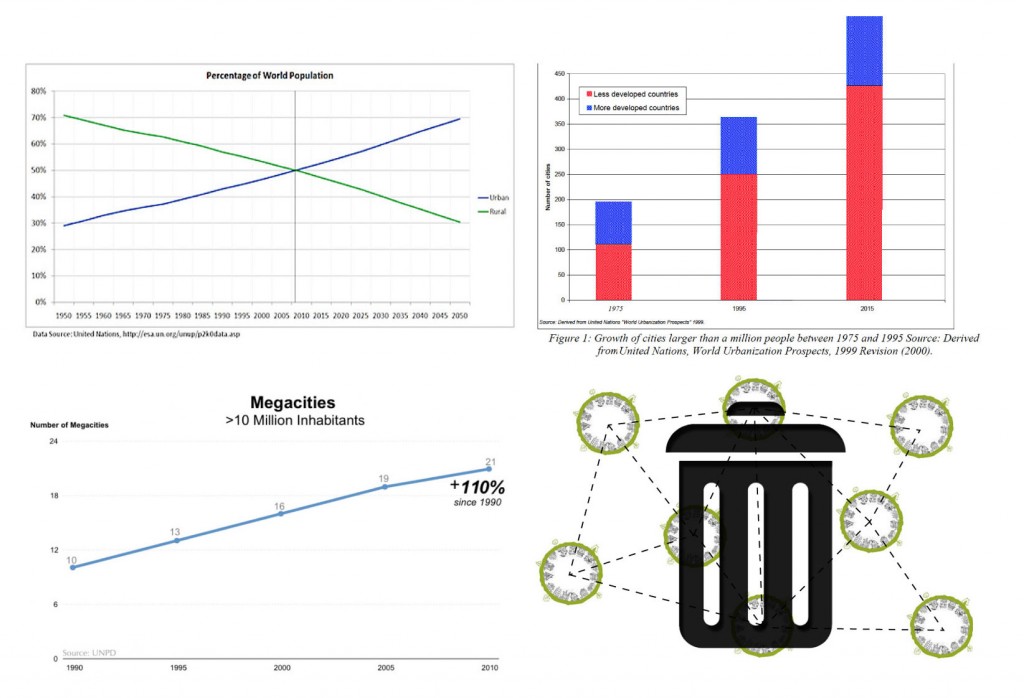

The idea of the city as a cluster of self-contained villages, while endlessly irresistible to urban planners, repeatedly defeats itself both in theory and practice, and should be tossed in the trash.

To take its place however, a new planners’ darling is emerging in the form of the “networked city”. In the networked city, the beloved villages genuinely are villages, in that they are spatially disaggregated, only they are now all hooked up via the internet. This enables the residents of the networked city to live variously in the Cotswolds, on the sea, by Lake Windermere etc., with their laptop, alternately working away in the global marketplace, and regaling themselves with the view.

To take its place however, a new planners’ darling is emerging in the form of the “networked city”. In the networked city, the beloved villages genuinely are villages, in that they are spatially disaggregated, only they are now all hooked up via the internet. This enables the residents of the networked city to live variously in the Cotswolds, on the sea, by Lake Windermere etc., with their laptop, alternately working away in the global marketplace, and regaling themselves with the view.

The idea that this will happen is in fact not so new. It finds its precedent, as does the technology, in the telephone. When the telephone was first rolled out, it was predicted that no one would bother to leave their home any more, the need for transport would implode, and people would live ever more remotely. What happened was in fact the complete opposite. The telephone provoked a transport explosion, as people called each other, and immediately said, “Hey, let’s meet up!”

The telephone proved to be a net trip-generator, and the same is certainly true of the internet. While odd bits of online shopping result in some reduction in trip numbers, this effect is vastly outstripped by the plethora of new connections made as people social network, business network, online date, google search for things to do and places to go — all of which, if they lead to anything, more often than not lead to the need for a “flesh meeting”, and therefore, the need for trips to be made. Because of the physical trips, it’s easier if the people involved are close to each other, and the most convenient solution is thus for everyone to locate themselves in a large city.

Which is precisely what people are doing. While the internet is getting ever faster and more ubiquitous, urbanisation trends are equally relentless. The proportion of urban to rural residents tipped over the global 50% mark in 2008, and continues apace. Moreover, the urban locations people are flocking to are the large ones: cities of over one million residents are rising fast, as are megacities of over 10 million. London is looking to join the megacity club, posting a 12% population increase between 2001 and 2011 to bring the recent total up to 8.1m. Together these trends are enough to put the “networked city” firmly in the trash can too.

reading left to right: percentage of world population living in urban (blue) vs. rural (green) environments, 1950-2050; number of cities with population over 1m, 1975, 1995, 2015; number of cities with a population over 10m, 1990-2010; networked city in the trash

The effect of the internet on urban movement has been to increase the number of trips people make, and consequently the need for urban aggregation. But more interestingly perhaps, it has also increased the randomness of trips. This is due in part to the way the internet provides a medium for people to perform space-insensitive searches, and to make space-insensitive connections. Put less abstractly: if you are searching online for a particular business or social link, the internet will readily return results from across any geographical field you define (e.g. the city you live in). The likelihood as a result of finding yourself more aware of, and therefore potentially more drawn to, service-providers, restaurants, friends, dates etc. outside of your local area, is that much greater. The internet effectively collapses the distances that previously separated the raw information, and in so doing helps the city to operate as a unified market, and for customers, clients, employers and socialisers alike to have equal access to knowledge about who and where each other are. If the knowledge then precipitates a trip, as often it will, the next point for the hardware of the city is to allow these people to get to each other, irrespective of where in the city they start out, and whether or not they’ve travelled that route before (or will again).

This randomness effect is in fact augmented by the “networked workforce” concept, in that while technological networking doesn’t support people extracting themselves from the city entirely, what has been falling off is the extent to which people work in a single stable place within the city. Flexible working practices lead to people increasingly working in part from home, in part from cafés, travelling around to have meetings in different places, hot-desking in different hub locations, etc.. As a result, the workplace is becoming less one place than a set of disparate locations distributed randomly across the city. This effectively does away with the predictability (from the transport planner’s perspective) of the traditional work-home commute.

Worse still, the trend is now for people to change jobs more often, wanting less a job for life than a job to get them to the next stage of their career. Consequently, the likelihood that the location of their home will be rationalised in relation to their place of work is considerably reduced. In the stable desk-based job-for-life era, it was easy enough to buy a home near a station on a direct link to wherever your office was. But if your office is constantly moving around, through the twin forces of flexible working practices and frequent job-switching, it’s really not so straight-forward.

So what does all this suggest? Three principles emerge. Firstly:

1. Both urbanisation and technological trends indicate a strong move toward larger cities, characterised by more trips, to increasingly unique destinations, of a continuously shifting and fundamentally unplottable nature.

With the trashing of the “village-within-a-city” and “networked city” concepts, we return to the unified city as the only viable model, with its essential reliance on high levels of internal mobility. Urbanisation evidence shows this model to be strongly favoured, while technological and social change all increase the demand not only for mobility, but for free, unfettered, non-linear, unidirectional mobility.

So how does the city cope with this? On the one hand, there seems to be the city’s almost inexhaustible ability to generate desire among its residents to make connections and trips — indeed this is its strength. However the city rapidly runs into congestion problems as the physical infrastructure fills up. Both the congestion and related costs accrue, creating trip aversion, which cuts back against trip desire. Thus principle two:

2. The city achieves a homeostasis between trip desire and trip aversion. This is its congestive capacity.

Congestive capacity is reached at the point where the desire of residents to go to places is balanced out by how expensive it is, how long it takes, and how uncomfortable the ride. The specific level of congestion at which this congestive capacity is reached will vary from city to city, and depend on things like economic factors, demographics, local culture etc.. The essential point however is that cities should expect this congestive capacity to exist. Increasing or decreasing, for example, the volume of infrastructure (such as by building more roads) will not lead to dramatic changes in the level of congestion, as the number of people using the infrastructure will increase or decrease accordingly, thereby returning it to the previously established level of what residents will happily tolerate. Given this idea of a congestive capacity, and adding it with the earlier premise that the city’s key advantage lies in its provision of access, leads to principle three:

3. The more trips the city is able to process when operating at its congestive capacity, the more efficient and competitive the city.

And this one is the killer, because the standard way to frame the debate around congestion is to ask continuously, “How can we reduce it?”

The most obvious way to achieve a reduction, in the face of strong trip desire, is to increase trip aversion, thus lowering the level of congestion at which congestive capacity is reached. But this cuts into the volume of trips being processed, and so injures the city. This is the paradox of contemporary transport measures.

On one level, it is astonishing how many people involved in urban transport approach it from the position that the fact of people moving is somehow the problem, and the best transport solution would therefore be to get them to stay at home. And while such a position is rarely stated explicitly, the urge to somehow negate “excess” movement is frequently at work within congestion curbing measures. Yet the real effects of such negation are rarely considered.

In a typical cost benefit analysis of congestion, the hours people spend in stuck in traffic appear on the cost side of the ledger, monetised at an average income rate (or some equivalent). But what this fails to account for is the counterfactual — i.e., if those people don’t make those trips, and are therefore not stuck in traffic, what are they doing with the time instead, and are they really monetising it at their average income rate? Because if they stay at home and, say, meditate, this may be beneficial for their well-being, but it certainly won’t result in an overall gain in urban GDP (as the cost benefit analysis would try to suggest). Conversely, when someone makes a trip, the likelihood is they are going to engage either in some kind of productive work (to deliver a service or product, to have a meeting etc.), or some kind of consumptive activity (to have dinner, go to a movie, go shopping etc.) — i.e., the trip leads either to spending or making money, and so contributes to urban GDP. The traffic is a crucial part of how the city achieves its turnover, and knocking it out knocks out much more than a time cost.

Nevertheless, negation-based aversion strategies are frequently favoured, not least because they are the easiest ones to imagine. The easiest of all is to impose additional costs, such as the introduction of, or an increase to, a congestion charge. Congestion charges unsurprisingly are unpopular, not least because the trips they bite into are inevitably those made by people who don’t have the money to pay. The move toward making driving in the city less and less affordable, and more and more a preserve of the wealthy, is not only hideously undemocratic, but oddly ironic. The era of mass production, and of making sophisticated products available to a wide range of people, was driven in no small way by Fordism — i.e. by the opening up of economic access to the benefits of, precisely, the automobile. Just over 100 years on from the introduction of the Ford Model T, it would seem to be a shame now to start rolling back — not cars — but instead roads, to the rich.

It can of course be argued that if someone doesn’t drive, the trip itself needn’t be negated, nor the access lost. Instead, costing people out of cars, 100 years on the the Ford Model T, can be thought of as a progressive measure. After all, it’s a new century: we’ve now seen all the ways in which cars can be damaging to cities, and we should have some better ideas. Bringing down the number of cars on the road needn’t reduce the ability of the city to process trips. Quite the opposite — trip numbers can be maintained or even improved by boosting the uptake of other transport options. In essence, the trip aversion implicit in a car trip can be increased so long as there is a corresponding decrease in the trip aversion of using another mode of transport.

With this in mind, I want briefly to run through a couple of these other modes, and to think about how they match up in the specific case of London.

The first one naturally is public transport, which in London is phenomenally expensive. In terms of cost, and relative levels of aversion, public transport and driving a car into London come up surprisingly even in some ways. An annual zones 1-6 travelcard is priced at £2,136. It’s less commonly bought in this form however than as twelve one month travelcards, yielding an annual cost of £2,461.20. In comparison, paying the congestion charge every weekday of the year, minus public holidays when it doesn’t apply, and less 5 weeks holiday a year, comes in at £2,260 — just under the median of the annual/monthly travelcard range.[1]

The other point to make about public transport in London is that it is currently fairly full. If people were all to jump out of their cars, would the tube realistically be able to take them? Rush hour tube trains are unquestionably crammed. Moreover they run fairly frequently, and the frequent system failures would suggest that Transport for London’s immediate ability to up the number of trains running at rush hour is at least questionable. Aversion techniques can again be brought in to try to persuade people not to travel at rush hour, and peak fares exist to do precisely this. However, the ability of people to travel at rush hour is critical to the functioning of the large urban labour market.[2]

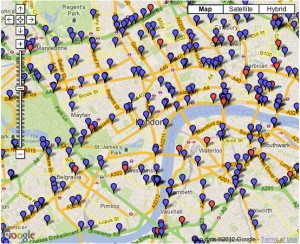

The next option is the bicycle. Here cost is very low, but there is a different aversion factor at work in the form of safety. Below is a Googlemap showing cycling accidents in a section of central London. The blue pins indicate serious injuries, the red pins fatalities.

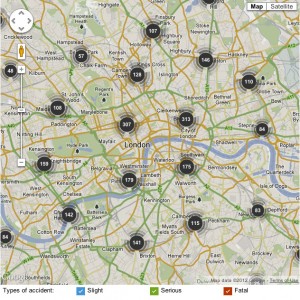

The map is impressive as it shows the spread. Note in particular how accidents are not so much clustered in “black spots”, which could be addressed or avoided, but rather are distributed fairly comprehensively throughout the network. It’s an slightly old map though, from 2008. Here is a more recent one in a slightly different format:

The map is impressive as it shows the spread. Note in particular how accidents are not so much clustered in “black spots”, which could be addressed or avoided, but rather are distributed fairly comprehensively throughout the network. It’s an slightly old map though, from 2008. Here is a more recent one in a slightly different format:

The numbers, covering August 2011 to July 2010, are astonishing: 179 accidents in Westminster, 307 in the West End, 313 in the City, 175 in Southwark. These includes slight injuries, serious injuries and fatalities. If we take it down to just serious injuries and fatalities, it looks like this:

The numbers, covering August 2011 to July 2010, are astonishing: 179 accidents in Westminster, 307 in the West End, 313 in the City, 175 in Southwark. These includes slight injuries, serious injuries and fatalities. If we take it down to just serious injuries and fatalities, it looks like this:

Again look at the numbers: 22 in Westminster, 25 in the West End, 45 in the City, 26 in Southwark. Well over 100 serious injuries or fatalities just in the very centre of London in one year. It’s brutal. Who would ride a bike? Or recommend their children ride bikes?

Again look at the numbers: 22 in Westminster, 25 in the West End, 45 in the City, 26 in Southwark. Well over 100 serious injuries or fatalities just in the very centre of London in one year. It’s brutal. Who would ride a bike? Or recommend their children ride bikes?

There is no doubt the cycling infrastructure in London leaves an enormous amount to be desired. The key strategy over the last ten years has been to paint either green or blue stripes along the sides of otherwise unchanged roads — an intervention which is almost entirely cosmetic. The chief effect has been that motorists can now enjoy driving with two of their four wheels rolling over green or blue, as opposed to black, tarmac.

The promising thing about this however is that a real effort to improve the cycling infrastructure could lead to significant gains in safety, and a corresponding decrease in trip aversion to using this mode of transport. Notably bicycles are a far more efficient use of urban road space than cars, and so the same road network could process many times more trips, with corresponding gains in mobility and competitiveness (think of the number of cyclists that can pass through one cycle of a green light as opposed to how many cars get through in the same time).

However, as a magic bullet, cycling does have its limitations. These are imposed by the fact that a good proportion of urban trips are hard to convert to cycling because of an essential unsuitability of one kind or another. These include trips made by travellers who are, for example, elderly, infirm, obese, disabled, or underconfident. With clinical obesity alone accounting for 26% of the UK population and rising, this is already a sizeable group. But it goes on. Cycling is often unsuitable for people travelling with children, and children’s things; or with babies, and babies’ things (e.g. nappies, bottles, wipes, toys). Equally, getting rid of the baby, but keeping stuff as an issue, cycling is unsuitable for people who need to be transporting anything much, and so isn’t all that good for people going shopping. And, as in London you can anticipate bike rides of easily 20 minutes plus, quite possibly including a hill, and appreciable sweating, cycling can be unsuitable for people expecting to arrive at their destination at a high level of presentability. If you’re going to a business meeting, or a date, or a party, or want to wear a dress, or smart clothes etc., then the bicycle can be a problem. And finally, aversion to cycling becomes significantly greater anytime that it’s raining, or looks like it’s about to rain, or looks like it might be raining around the time you think you’ll be wanting to come back. If you remove all these groups and trips from the register, then all of a sudden cycling appears as a much slimmer solution to the issue of urban congestion than is often made out.

Lastly walking remains, but walking implies a limited range, and throws you back to the village scale, and the village-within-a-city dead end.

So what is the point I am trying to make? Certainly that non-car transport options in London, in their current state, are underequipped to do much more. But more, that simply hammering away at car usage, which seems to be the prevalent strategy, is an upsidedown way to go about things.

To set them rightsideup: firstly I’d advocate for a substantial reframing of the approach to transport and congestion. Congestion is best seen as a powerful indicator of a healthy city operating at full capacity. Cities that are free of congestion tend to be ones either in eerie free fall or political lockdown. On the other hand, cities that suffer from congestion are typically full of people trying to get to places to do things. If we embrace congestion as a condition of dynamic urbanism, we can start to move on.

The appropriate question then to ask is not how to reduce congestion, but how is it possible, given congestion, to maximise the number of trips the city is able to process at minimum cost, and minimum incidence of serious injury or death? The role of transport planners is therefore to focus on increasing transport efficiency. Measures that work up costs or other forms of aversion should only be considered if they can be balanced by the provision of credible alternatives, and trips negated by one mode should be more than compensated for by trips created by another. People are in the city essentially because they want to move — because they want to have access to the benefits the city offers. The responsibility of the city is therefore to provide safe, cheap, attractive transport options covering the full range of people who need to get around.

These points are in truth elemental and crushingly obvious. They are also bizarrely underaddressed. If we can move from a congestion-is-a-problem, we-need-to-stop-people-travelling, trip-aversion-driven form of thinking, to a solutions-orientated, maximise-processing, trip-desire-embracing form of thinking, then the chances of coming up with ideas that offer real alternatives, as opposed to just disincentives, are that much greater. The truth is cars are a very inefficient way to move around cities, and should be easy to beat. But instead of focusing on getting rid of them, we need to concentrate on putting in something better. And as soon as one large city is able to do this, the others may indeed cluster to whisper, “I like the way you move.”

Adrian Hornsby

Speech delivered at the House of Lords, UK, 16/10/2012

for the conference ‘Cities of the Future: Smart Ways to Move’

organised by Vision

—