At the top of the frontispiece of Bach’s infamous series of pieces for keyboard in all 24 keys, C major through B minor, revolutionary in its day and widely credited as being the beginning of Equal Temperament — a system of tuning which allows one to play pieces in remote accidental rich keys without sounding rubbish and thus the foundation of the Western Classical Tradition — Das Wohltemperirte Clavier or Well Tempered Clavier, there is a large and apparently uncharacteristically whimsical squiggle:

There is also quite a hefty squiggle at the bottom but it is to the squiggle at the top that I wish to draw the attention of the reader.

According to Bradley Lehman this squiggle represents a system of tuning, an unequal temperament and Bach’s preferred system for tuning a keyboard on which to play his seminal instructive work. In other words the so-called foundation of Western Classical Music is based upon a system which, rather than being sensibly equal and precise, appears to be decidedly wiggly and skewiff.

Apparently Das Wohltemperirte Clavier was submitted by Bach as part of an application for a teaching post in Leipzig and at the time musical education included learning how to tune a keyboard. He was simply including his own tuning system as part of his application.

It makes perfect sense. Turn the page upside down.

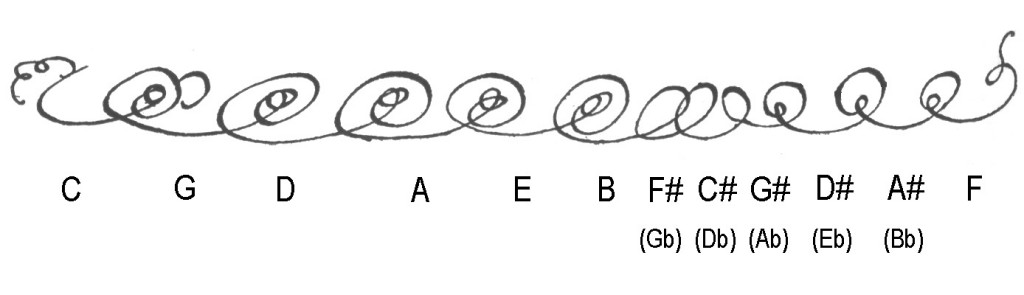

Each of the twelve big loops represent one of the twelve semitones in an octave arranged in a cycle of fifths from left to right. Next to the first squiggle is a C. This orientates us at C on the keyboard. The C squiggle consists of 3 little loops inside a big loop. This indicates that the first fifth in the cycle, the interval from C to G, rather than being tuned ‘pure’, i.e. with a frequency ratio of exactly 2:3 such that it gives a clean, glowing sound, should be a bit off. Actually three bits off. Precisely three squiggles sharp of a loop.

This applies also to the next four fifths. G to D three squiggles. D to A three again. Until we get to B. Now from B to F# — no squiggles. Empty loops denote pure fifths as far as C# and then G#. And hereafter? A reverse big loop with just one squiggle inside for the fifths to D#, A# and finally F which is to say one squiggle flat of a loop for these.

And there we have it. In a single stroke in Bach’s own hand. What more elegant way for the father of music as we know it to graphically describe a lifetime’s experience of sound? What better proof of the folly of academia that for hundreds of years scholars have mistaken the transcendent true principle for a decorative flourish while crediting the genesis of an entirely different system of tuning to the very same work?

There is no doubt in my mind that Bradley Lehman is correct in his analysis. For his full article see http://www.larips.com.